Out of stock

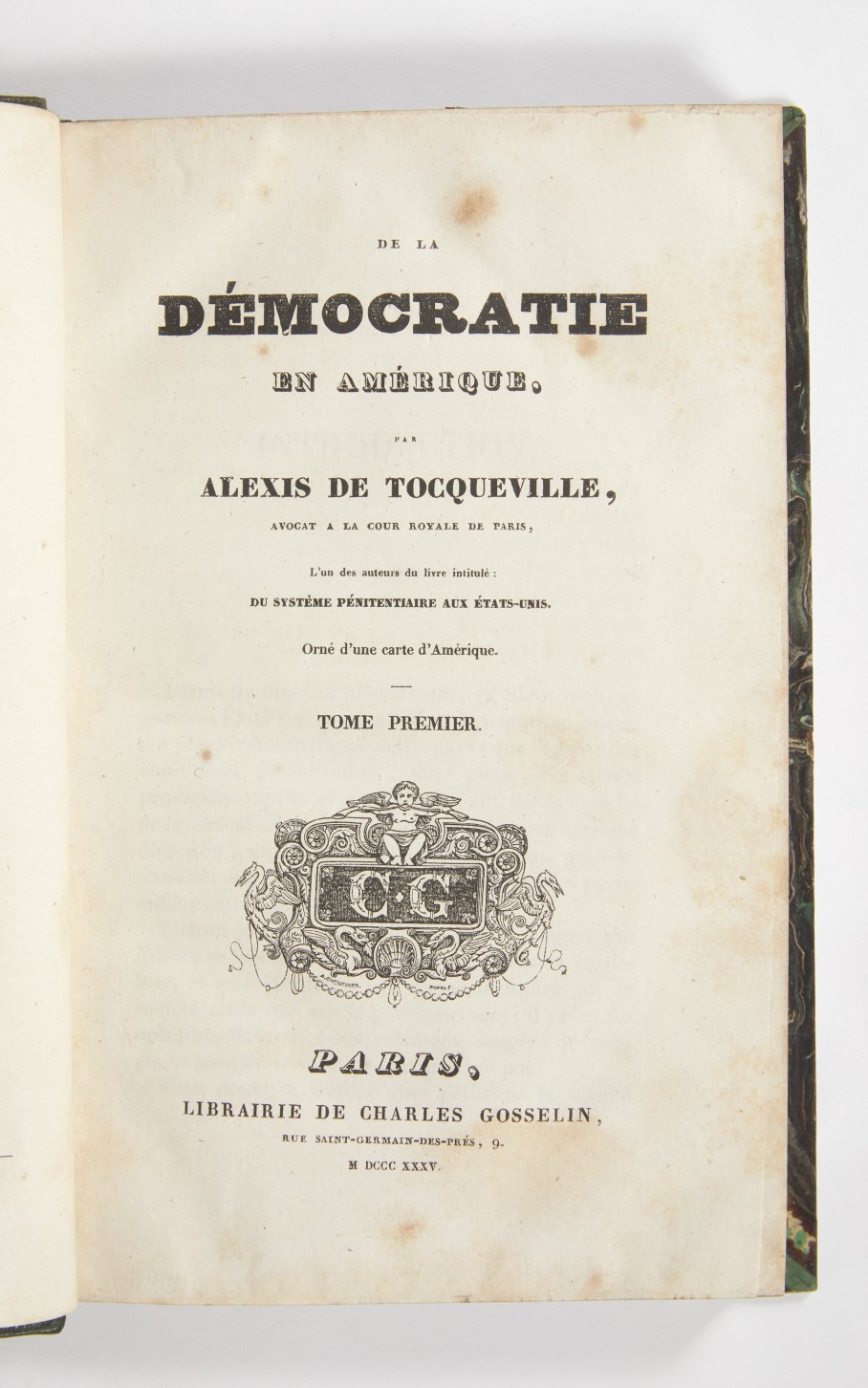

First edition of Alexis de Tocqueville’s masterpiece, published in two parts (each in 2 volumes), respectively in 1835 and 1840. While part one was printed in a very exclusive print run of only 500 copies on laid paper, part two benefitted from the success of the previous portion and was printed in 1000 copies on wove paper. The book was such an editorial success that, on the publishing of the first edition of part II, the first part was already at its 8th edition.

“Alors qu’ils étaient magistrats à Versailles, son ami Gustave de Beaumont et lui-même se firent confier la mission officielle d’aller le système pénitentiaire des États-Unis (1831-1832). Tocqueville put ainsi observer concrètement la démocratie dans le seul grand pays alors en république. En janvier 1835 il publia De la Démocratie en Amérique (Gosselin, 2 volumes) où il décrivait la société politique américaine et concluait que la liberté humaine pouvait surmonter les périls présentés par la société nouvelle. En avril 1840, Tocqueville publia la suite de l’ouvrage (2 volumes) consacrée à la “société civile”. Si la portée des volumes de 1835 dépassait déjà la seule Amérique, cette fois celle-ci ne faisait guère que fournir des exemples. L’auteur en réalité, avec une audace novatrice, construisait un “idéal-type” de société démocratique au sein de laquelle il s’efforçait d’imaginer l’horizon intellectuel et sensible, et les moeurs du futur homo democraticus” (André Jardin, in: En français dans le texte).

“Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” is unanimously considered to be one of the most famous foreign attempts to comprehend the ideological basis on which American society rests and to coherently explain its political and societal implications” (Sigrid Karin Amos, in: Alexis de Tocqueville and the American National Identity: The Reception of De la Démocratie en Amérique in the United States in the Nineteenth Century, 1995).

“Until Alexis de Tocqueville published his De la Démocratie en Amérique in 1835-1840, democracy was almost invariably taken to be direct democracy practiced in small communities, such as ancient Athens or eighteenth-century Basle, and democracy and representation were seen as opposed forms of government. In the wake of de Tocqueville’s book, the concept of democracy became rapidly connected with the concept of representation, and in 1842 – before the abolition of slavery – the United States were praised as the most perfect example of democracy” (Mogens Herman Hansen, in Ashgate Research, Direct Democracy, Ancient and Modern).

“In the opening pages of Democracy in America (1835), Alexis de Tocqueville explained his awareness of the acute necessity for a novel theory in the society which was emerging in the New World. In the new age, ‘the equality of conditions is the fundament fact from which all others seem to be derived and the central point at which all my observations constantly terminated’. Tocqueville would not have suspected how accurate these remarks would still be, on the other side of the planet, two centuries later. Not only do the requirements carried by ‘the age of equality’ extend to other societies than those spawned by the European or North American industrial revolution, but they can also prove of great analytical importance in the depiction of the logic of family law reform in the Muslim world of the twentieth century. In the Tocquevillian axioms of the age of equality – gradual, universal, and irreversible – can be found the fundamental principle against which developed the codification of family law in countries with a significant population of Muslim citizens; the equality of women and men before the law” (Chibli Mallat, in Introduction to Middle Eastern Law, p. 355).

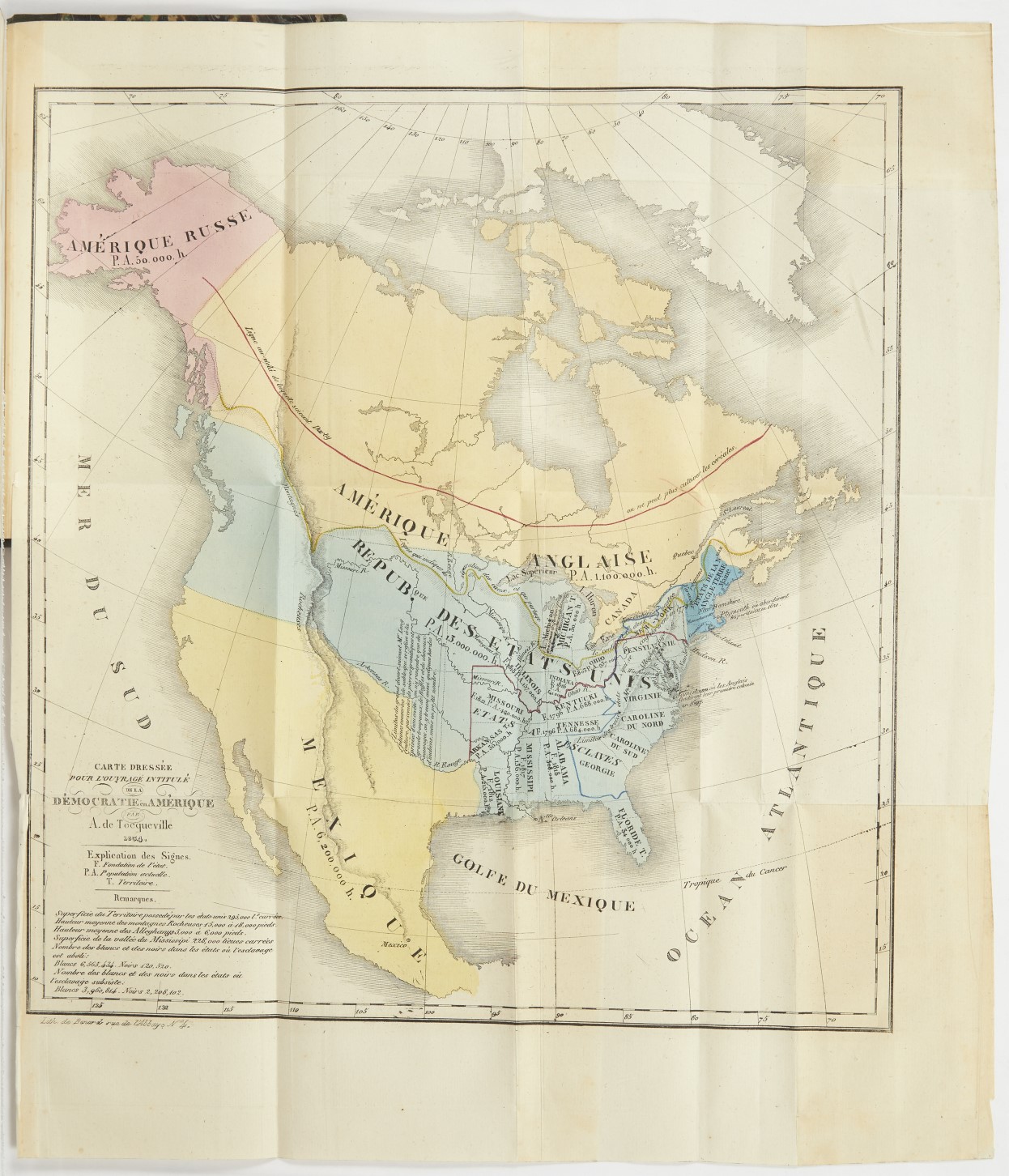

Sets uniting both parts in first edition, and preserved uniformly bound at the time – such as the present one – are of the utmost rarity. It is complete with the large folding map, lithographed by Bernard in 1834 and coloured in outline. Some occasional foxing, small tear to map at gutter.

Vous pourriez également être intéressés par ...

Related products

-

BRÉBISSON, Alphonse de

6 000 € Add to basket

Nouvelle méthode photographique

1852 -

BLANQUART-EVRART, Louis-Désiré

30 000 € Add to basket

La Photographie

1869 -

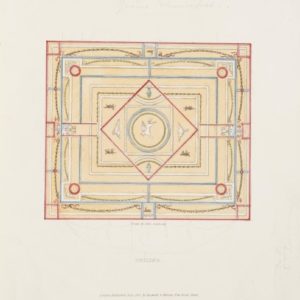

GOLDICUTT, John

3 800 € Add to basket

Specimens of ancient decorations from Pompeii

1825 -

BURNES Alexandre

2 800 € Add to basket

Voyages de l’embouchure de l’Indus à Lahore …

1835